Confession #20: Not Guilty Does Not Mean Innocent

Me and OJ, Thirty Years Later

Warning: I almost didn't release this piece. Please handle with care. On October 3, 1995, I was a recent high school graduate assembling sub sandwiches on the long, white deli board of a bustling pizza joint. There was a small TV hung high in the corner of the checkout area that played the news every day through our busy lunch rush. 30 years ago this morning, I stood there in a hushed crowd watching OJ Simpson face his jury.

Boy, time is a funny thing.

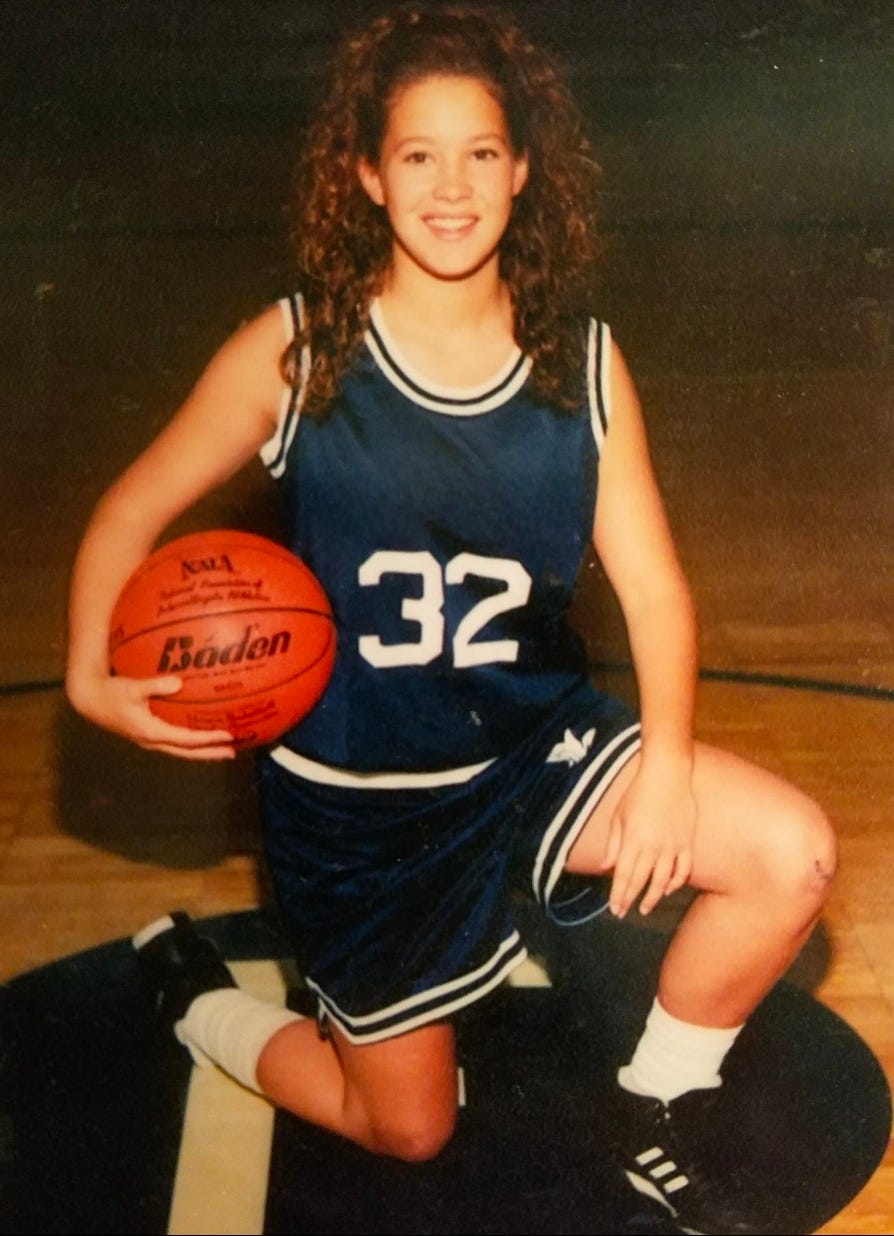

Perhaps the most infamous verdict of our lifetime, its details are still retrievable— brown suit, Johnny Cochran, that relieved smile. But ask me to go back one year prior to my own trial, and memory fails. Before OJ, I was a 17-year-old girl who had been ordered to stand and face a jury on charges of negligent homicide.

Three decades later, I am still processing.

You would think that I have already wrestled and wordsmithed this story by now. You could assume that I, writer of criminal justice and matters of consequence, have already told about my own courtroom drama in great detail, but I have not. Only those closest to me have ever heard about the events of May 25, 1993— and though it was never my intention to hide it, maybe I have been avoiding it somehow.

A few weeks ago I was at my desk writing about some justice-related thing when in a shock of realization, I sat bolt-upright and took a sharp inhale. I have been a defendant, I thought. It was like emerging from amnesia. A sudden cascade of recall spilled out and all around and I plunged headfirst into a dizzying series of connections. The moments that followed took my breath away.

With God as my witness, I have never thought to share any of this with you until now and after considering it over the past few weeks, I understand why my subconscious kept it boxed on a shelf deep in a closet somewhere. This is the hardest thing that I have ever written.

I had only had a driver's license for four weeks when one of my best friends tumbled from the trunk of a car and hit his head on the pavement, causing his death. I was the stupid girl in the driver’s seat of the car from which he’d fallen. I stood there helpless on the side of the road, unsure what to do, and watched him struggle to take his final breaths. Breathe, I begged him. Please, get up. Please.

When the paramedics arrived and I knew that it could not be undone, I ran to a neighboring house to call his mom from a wall phone. He's gonna be okay, I told her, and I had the audacity to believe that.

The next morning, he was taken off of life support and some time in the following weeks I was formally charged with his death.