Confession #10: Coffee is Life, Literally

Commissary, Part 1

*This post contains graphic descriptions of bodily functions. In casual conversation last week, I heard someone refer to a U.S. Army base grocery store as The Commissary. My brain hiccupped and for a moment, I was in a prison cell.

This happens almost every day— these prison teleportations.

I had forgotten that commissary is a term used by respectable people in honored places. That concept was buried deep within my psyche, packed away with all of the other innocent associations I once held. These days commissary is evil, albeit necessary. It is also a PITA:

Can I get some money on my account this week?

Store is due on Tuesday.

I need to get some in my next store.

There is so much to say about the realities of helping someone inside buy goods to survive that I have decided to divide this topic into two separate posts: The Necessary and The Evil.

Let’s begin with necessity.

Commissary offers one glorious moment of autonomy in an otherwise option-less prison life. It affords a modicum of comfort— if off-brand honey buns can be considered comfort. It will buy status, if one plays that way but mostly, it provides our loved ones a pinch of dignity and sanity while warding off the gnawing gremlins of hunger.

When I was working full-time, I arranged an auto-deduct from my account into his which covered basics each month. Once I got ill and stopped working, the auto-deduct stopped too. The requests are minimal now; I just need some coffee and a few toiletries.

An 8 oz. package of instant Maxwell House is $11.10, and he will go without food to get it. They do not get coffee in prison unless they buy it or barter or luck into the benevolence of a cellmate who is willing to give up a shot.

Prison’s retail market is a booming business. It is estimated that an American inmate spends about $1000 a year on canteen food, hygiene products, and clothing supplies. The Prison Policy Initiative estimates that non-incarcerated American families spend approximately $2.9 billion annually on commissary and phone calls for their loved ones.

While it is normal for those outside of this mess to point to the ‘availability’ of prison employment for income to buy their goods— some states do not pay inmates (here’s looking at you Texas, Georgia, Alabama, and Arkansas). If they are paid, the average prison wage is .10 to .86 cents per hour.1

A pack of Ramen noodles from commissary is .52 cents.

Every two weeks, The Prison Store opens up. My son has to have both the money and his completed, formal list turned in by Tuesday to procure his things— let me clarify, he will get his order 10 days later. It has taken me over two years to dial in the scheduling of this thing— Order by a certain Tuesday. Get that order 10 days later, on a Thursday. Make that food and those provisions stretch for three weeks until the next order, which was placed on the intervening Tuesday, arrives on the 3rd Thursday. Like everything in this system, it is mind-numbingly complicated and inexpedient.

My son is allowed to order up to $130 worth of goods at a time, two times a month. Until this blog started and your subscriptions filled the gap, he often only had $80-100 per month to spend. Thank you, thank you, thank you. For inquiring minds, he orders pre-packaged food items to make cook-ups2 as well as toiletries, undergarments, socks, thermals, shoes, paper, pencils, stamped envelopes, and coffee. Did I mention the coffee?

Though it’s mostly cheap crap, it is not marked at Dollar Store pricing—

Ruffles 5.5 oz. Cheddar & Sour Cream Potato Chips $3.88

M&M’s 5.3 oz. Plain Candy $3.96

Generic Peanut Butter 18 oz. $4.16

Libby’s 16 oz. Cut Green Beans (4 PK) $4.69

Kellogg’s Club Crackers $7.26

Toothpaste $5

Deodorant $3.50

Yep, inflation has hit prison populations too.

There are Reddit pages, Instagram accounts, and Facebook groups dedicated to commissary food realities. It is a small relief that returning citizens can joke about their former food struggles. Some report that they still crave a few of the convict-cookups they survived on— namely, the pepperoni stuffing and infamous Ramen and Shabang chip creations.

For his birthday this year, I sent my son the only gift he is allowed: books. One was a cookbook by a fellow inmate. Anthony Duke is a Michigan prisoner doing Life Without the Possibility of Parole (LWOP) for a crime that he likely did not commit. Listen to that incredible story here.

This book is available on Amazon and makes a lovely gift for the starving individuals in your life. Buy it here. In a fun twist, your purchase will help fund Mr. Duke’s commissary.

It Stinks

I assumed, in my era of innocence, that the incarcerated were provided basic hygiene necessities in the U.S.. They are— kinda.

The state (or federal government) provides travel-size toiletries each month3. The quality and quantity are questionable. Depending on one’s security level and other determining factors, an inmate is typically issued one small soap (or body wash that doubles as shampoo), a small toothpaste, and one roll of 1-ply, institutional grade toilet paper per week. Having a heavy period? Not their problem. Diarrhea? Too bad, ask your neighbor.

Toilet paper is not a guarantee behind bars and, if not protected, it will be stolen.

Dental floss, hair gel, lotion, conditioner, Chapstick, nail clippers. None of these are provided without private purchase from commissary.

Even deodorant is not state-issued.

Though policies vary from state to state and county to county, deodorant is not explicitly listed as a provided hygiene item in American prisons. In many cases, an “indigent kit” can be sought after one applies and qualifies under certain criteria. Spoiler Alert— if you have funds from family in your account, you do not qualify.

So— people like my son are living 23/7 in a cell with another individual or several individuals who don't wear deodorant. Also, at this level of restriction, you only get 3 showers a week.

Speaking of showers, let’s do a fun thought-experiment: You are let out of your cell for a few minutes to walk across cement floors to enter the ever-damp shower which dozens of other people of all ages, sizes, smells and ‘habits’ use. Your mom didn’t get to pack you flip-flops. Do you call home to ask for $5 to get some shower shoes in your first commissary order or wait and pay for fungal cream later?

Ladies

My gratitude for today is that I do not have a daughter in prison.

In this country, we do not yet (in 2025) have a shared understanding about inmate access to menstrual products. The fact that we need to enact legislation for human beings to be able to consistently catch their own bodily fluids is telling of our collective mindset around “corrections.”

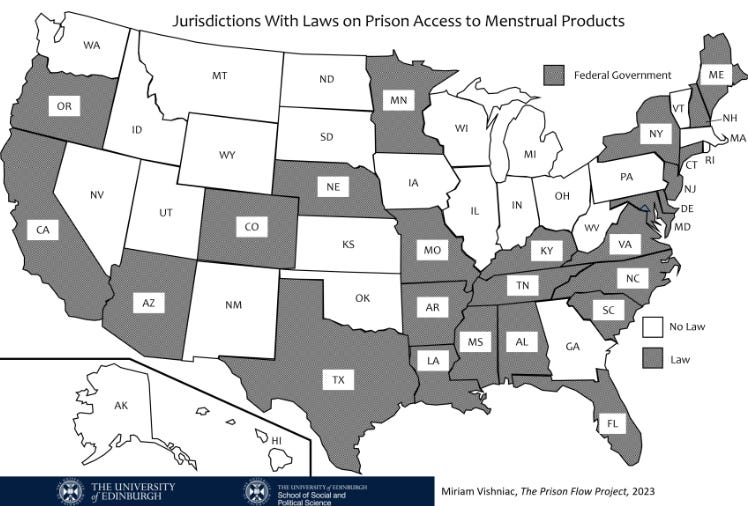

The graphic below marks the grey states as those who have relevant laws on the books. Those in white leave period product availability up to the discretion of local policy directors or, more likely, the warden of the moment. While your local grocery store places pads and tampons in the men’s room for free, bleeding women in prison are going without. #perspective #wholefoods

Imagine having to beg every month for a handful of flimsy, non-absorbent maxi pads with virtually no adhesive. Stories of bloody pads falling out of baggie prison pants onto communal floors are common. As you can imagine, this impacts one’s ability to perform a prison job, go to a family visit, or attend court dates with any level of focus. As any 7th grade girl knows, it also decimates your general self-esteem.

Even if we can somehow convince ourselves that this inhumane and humiliating reality of prison life is in place to serve as a deterrent to those who might want to return to such a God-awful place (research indicates it does not), they are called sanitary pads for a reason. Not having consistent access to stop the free-flow of biological matter from a hole in your body is, above all, a disturbing public health issue. No thank you to uterine lining on shared visiting chairs.

“So UsE A TOwEL!” some heartless online commenter writes. That is not allowed. It is considered damaging State property. Women are punished and fined for it.

So— commissary to the rescue. Right now, in our state, a name-brand box of 36 super tampons is listed for $9.19. Will it be coffee or tampons this month?

Ironically, our state “Prisoner Guidebook” requires that all prisoners “maintain a ‘well groomed’ appearance.” Well-groomed expectations include the condition of your clothing, for which you are responsible to arrange laundering. While laundry services exist, I hear tell that many individuals prefer to wash their things in their cell sink to avoid theft and contamination.

Washing up is, as a matter of fact, a cottage industry in prison. An enterprising person can barter dishwashing or cell-cleaning for canteen goods. Without people on the outside to send funds in, guys and gals have little choice but to become entrepreneurial. In the poverty of prison life, the cycle of breaking rules in order to survive continues. Should you ever find yourself on the inside, you didn't hear this from me— One of the cheapest items on any commissary list is dish soap. Do what you gotta do.

For inquiring minds, all new prisoners are issued—

3 pairs of socks

3 brassieres— women only or by request

2 undershirts

7 underpants (that’s the word the state uses)

2 pairs of thermal tops and bottoms

3 pairs of slacks/trousers

3 shirts

1 pair of shorts

1 pair of shoes (plastic, black)

1 set of pajamas

You get replacements only every six months if requested, but that is not a guarantee.

Replacement prison clothing is often pre-worn— complete with shit stains in underwear and cum in socks. Even if you get an unworn, new set of Underoos, they are so cheaply made that they are likely to rip out the first time you bend over to pick something up. Asking for a new pair will land you a “Destruction of State Property” ticket— and not a new pair. Yes, that is 100% happening.

It is easy to understand why buying a Hanes brand t-shirt and a $5 pair of cotton boxers from commissary might feel like splurging on Rodeo Drive.

Define Necessity

In another post at a later date, I will discuss the dearth of medical care, nay medical neglect, behind bars.

Over-the-counter remedies (e.g., antacid tablets, cough drops, vitamins, hemorrhoid ointment, antihistamine, eye drops) are not provided by the state. Before the staff at one of his facilities threw away his dentures in a cell move, my son needed denture cream to hold his teeth in place to talk and eat— it was not provided by the facility so I bought it for him.

On a good day in prison the nursing staff is overwhelmed, time-limited, and in many cases trained to remain unempathetic to the needs of their patients. Even if a doctor has approved it, requests for pain relievers and ointment often go unanswered. Insomnia, gastrointestinal distress, broken teeth, skin rashes, hemorrhoids, blisters, in-grown nails, and open wounds become chronic conditions for which inmates have to doctor themselves.

In these cases, (you guessed it) the trusty commissary is available to offer a cadre of physical care options at a 200% markup. A pair of “readers” costs $15 inside while Walmart offers the same pair for around $5.

Black Market

There is an even darker side to all of this. Like all enterprise, commissary creates disparity. Commissary divides people into haves and have-nots. You have stars on your belly or you don't— and there's a Sylvester McMonkey McBean on every block.

The recording artist Jelly Roll recently shared a story about his own use of commissary during his prison days— $50 back then built him a nice little prison income. Inmates who can find a way to stock up live (by their definition) well. As he spoke, though, Jelly looked back at his former realities with sadness, lamenting his inflated sense of security. He was worth nothing more than a pile of stored commissary goods on the day his daughter was born.

Within the first year of the ride, every mom of an incarcerated individual learns about the vortex suck of Cash App, baby mama money requests, store debts, and threats of violence.

Vulnerable, fresh meat always beckons predators. Young, first-time offenders do not know the terrain— They often get in over their heads, start to owe the wrong people money, and then feel forced into illegal activities or gang participation to survive. It's the machine inside the machine.

The moms are the ones who get the panicked phone calls and middle-of-the-night JPay messages asking for more money. The moms are the ones who figure out how to cover it. The moms are the ones who can't sleep and try to be strong and don't tell other family members about this darkness. I know a woman who finally, after months of pressure and stress, put up a boundary and refused to pay her son’s bullies another cent— She then buried her son after they killed him for his outstanding debts.

Her regret haunts me.

We can laugh about Ramen noodles, but people lose their lives over this stuff. This isn’t summer camp.

To Be Continued…

Once, while waiting in the lobby for a visit, I struck up a conversation with a kind vendor who was stocking the vending machines. He candidly told me that staff vending prices were different than prices for the incarcerated and their families. The same sandwich in the same building costs two different amounts.

Why?

Because COs won’t pay what the isolated and hungry will.

Shocker— Prison commissary and prison vending are part of a corporate monopoly tied to old money and our friendly politicians in blue and red alike. We shall discuss this evil in Part 2 next week. Please Note: If I am unalived before then, follow the money. 😉

As always, thank you for your support. Love, Bridget

In Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina and Texas — prisoners don’t get paid for at all for their labor. They’ve held tight to the concept of slave labor.

A cook-up is a homemade meal in prison consisting of commissary and bartered kitchen items. They are created by mixing ingredients in clean garbage bags, using microwaves or makeshift heating elements or radiators, and employing a lot of patience.

There is no guarantee, however. U.S. prisons are only required to provide ‘basic’ hygiene products with no quality nor quantity required. Some facilities will only supply to indigent populations meaning if you have funds in your account, you may not get soap without paying for it.

Thank you so much for sharing your journey and the truth in this horribly difficult and dark situation.

Unfortunately I've gotten an education on all of this since my sister has been incarcerated. When she first got to her cell, there was a used maxi pad stuck on the ceiling. She was in that cell for several days before being transferred to another. That maxi pad was never addressed.