Confession #21: I'm In A Mood This Month

In the middle of nowhere

I drove six and a half hours to see my son this week. They are keeping him in the middle of nowhere, beyond a 550,000-acre national forest— two hours past an interstate exit and an hour past a gas station.

Limited availability meant that we only got an evening visit, so I pulled into the parking lot at dusk in a cold rain, my bladder bursting.

Walking across the pavement, I could see dozens of little orange stocking hats bobbing in the distance behind the fences. The temperature has dropped significantly since my last visit, and they’ve transformed themselves into bright-headed birds— walking in circles with their clipped wings.

That night in the visiting room, my son and I talked about the fences around the jailbirds who might get an idea to try and fly. ‘You might make it over one, if you were really prepared and damn lucky,’ my son said, ‘but there’s no way you get over the next three. We aren’t going anywhere.’

As a kid in the '80s, I remember worrying myself a great deal about those ‘Prison Area— Do Not Pick Up Hitchhikers’ signs. I imagined it was a common occurrence that an escaped convict slunk out from behind the trees with a hobo knapsack over his shoulder. It might also have been the familiar, haunting tenor of Robert Stack or the crazed urgency of John Walsh's voice that trained me on words like ‘fugitive.’

Never mind that less than 0.4% of incarcerated people escape annually, and nearly all of them are recaptured within hours or days— alone and hungry.1 Headlines leave out that the vast majority of escapes occur from minimum-security or work-release centers— not the high-walled, dystopian facilities like my son’s. In fact, our state has not had a prison escape since 2014 (and that guy was re-captured in less than 24 hours).

It never dawned on me, until they drove my son into the middle of nowhere, that the Department of Corrections must have one hell of a sales team.

How else do you get small American towns to donate hundreds of acres of pristine, untouched land in trade for miles of unsightly razor wire? Who wants creepy warning signs up and down their quiet country roads?

Company towns, that's who.

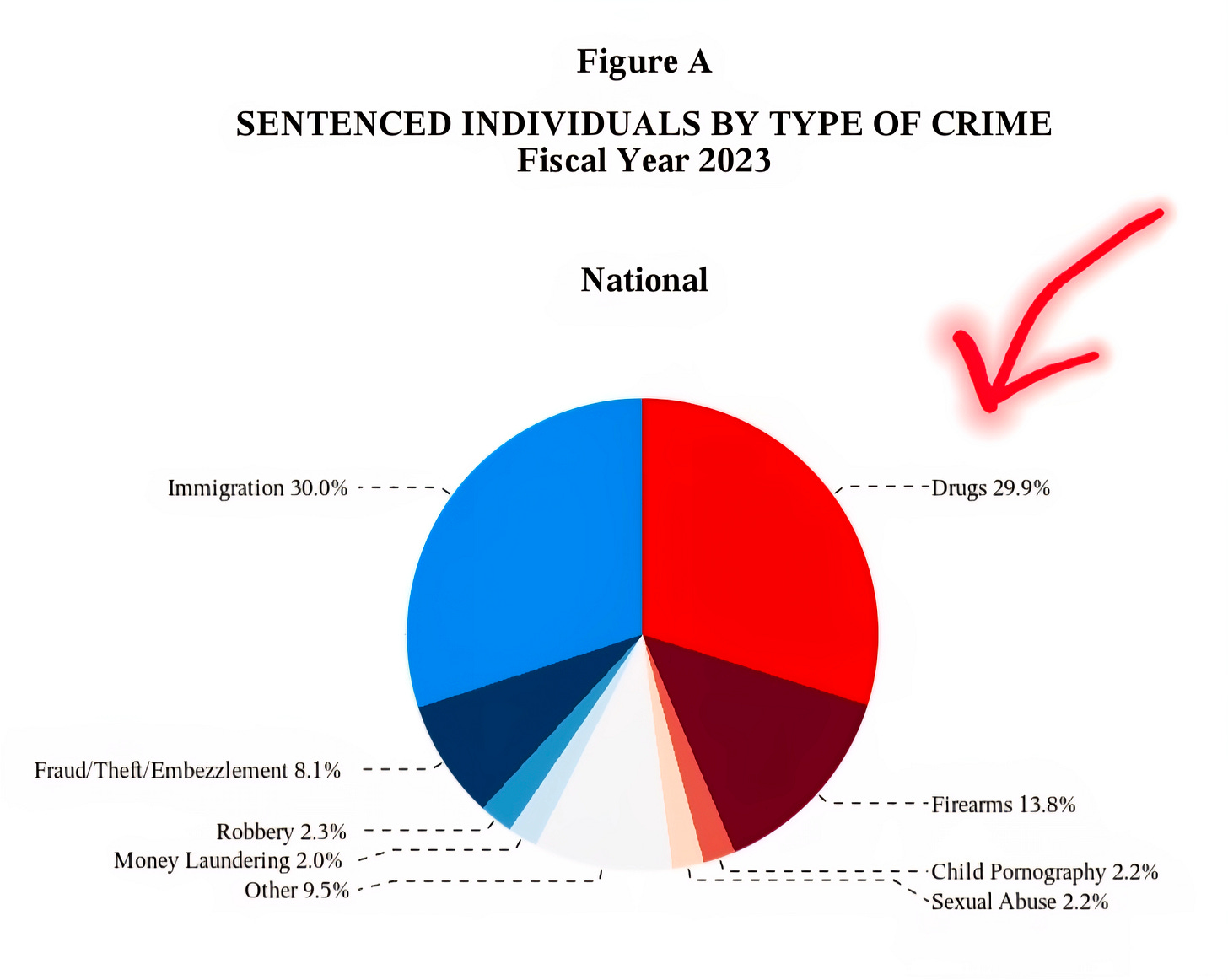

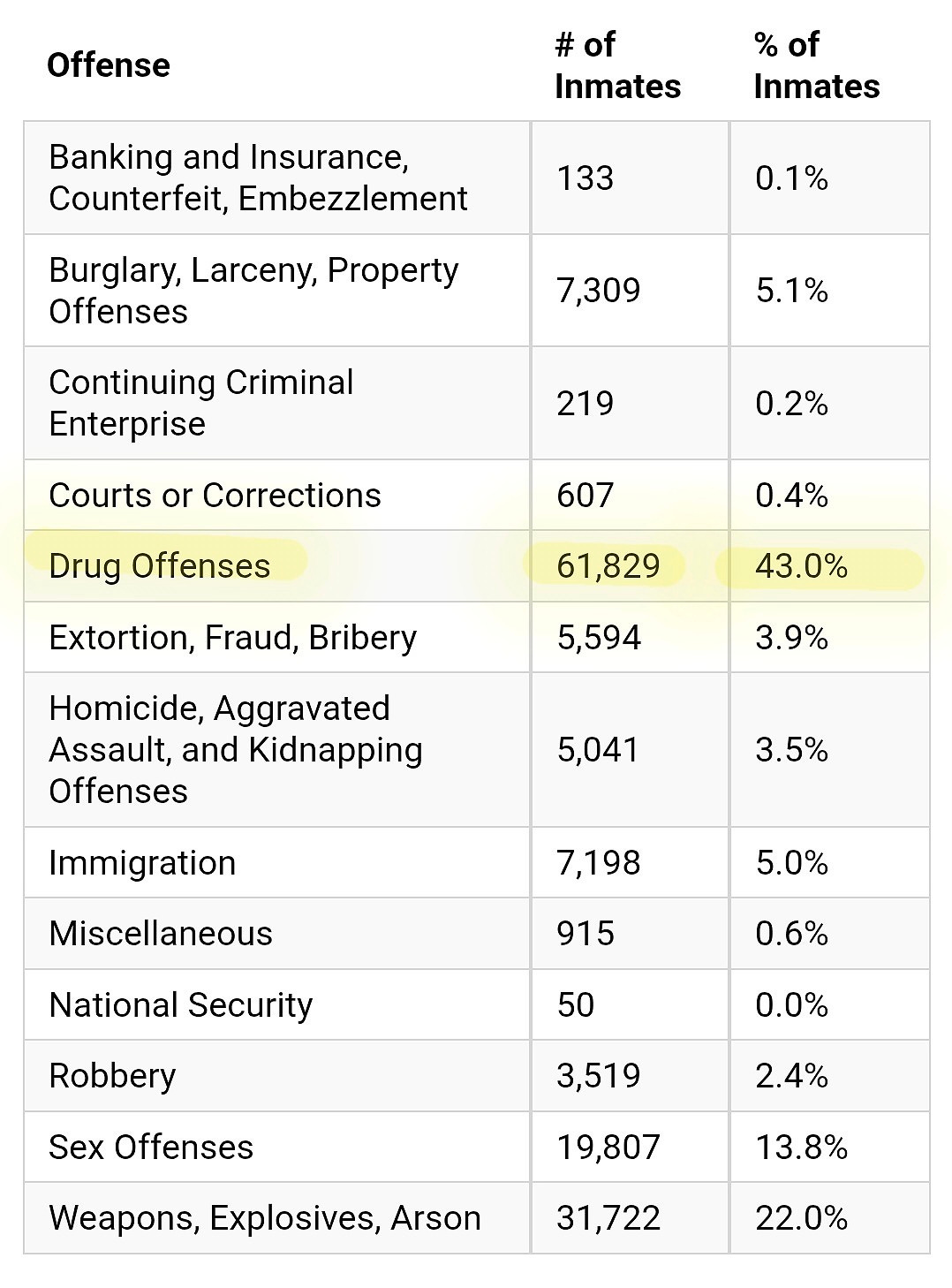

Prisons are nothing if not stable employers for villages that lost lumber and mining jobs last century. As fortune would have it, the War on Drugs brought a boon of industry roaring back. Prison marketers twisted a public health crisis into a security panic, which led to big public dollars funding thousands of new factories— the widgets on the assembly line, of course, being our addicted sons and daughters and mothers and fathers.

Make no mistake, the signs along the highway and the long drives into nowhere are an arm of the ad department. Carceral theater is pure psychological thrill because, in actuality, crime has been good for middle-of-nowhere USA. Keeping the boogie-man out of reach is keeping lots of rural folk employed. Who the hell would then care about the hundreds of thousands of wage-paying moms like me who have to drive a full workday to get two hugs and a shitty vending cheeseburger out of the show?

If I knew I wouldn’t be arrested for it, I would run those prison area signs over with my car.

Okay, clearly I’m in a mood.

As we enter the dark, dreary days of autumn and the Christmas music starts up again in stores, I slowly descend into an old foxhole where I curl up to conserve energy.

Down I go into resentment and avoidance— swearing to myself that next year will finally be the year that I take off for the Florida Keys instead of wrestling a wet, naked turkey in the sink at 6 a.m., only pretending that I am not grieving the life of one of my children who will, for yet another year, not partake in this gluttonous meal.

He would puke, I think, seeing how much food is about to be wasted— that his siblings will refuse leftovers when they leave and his favorite cheesy potatoes will be scraped in heaps into the garbage.

‘We’ll get our mystery-meat holiday meal though.’ he said with a laugh. ‘At least there’s pie or something resembling it this month.’

Meanwhile, I have my own mixed anticipations. I am waiting until the last minute to get my grandma’s old dishes out of storage because while I am still trying to give us all a sense of interconnectedness, she is gone now as well— a fact made worse by the memory that my son missed her funeral last year for this prison sentence.

‘I prefer to remember her the way I do,’ he offered. ‘I didn’t want to see her wasted away to nothing anyway.’ At least prison spared him some reality.

On my way home that night, I stayed under the speed limit. The thought of him being called from his bunk to be told by a prison chaplain that his mother died in an accident on her way home is just too much. You’ve no idea how many times I have quickly pleaded to the sky, ‘Please do not let anyone else pass before he can make it home.’

In spite of this annual autumn melancholy, I fully know the deal. Next year will come and I will pull out the plaid tablecloth again, look longingly at my deceased grandmother’s dishes, and stand there with my bare hands forming that damned, sticky cheeseball (the one my daughter loves) because for all of the support I give to my incarcerated son, I also harbor an inflated sense of duty to the children who will actually be at the table. Don’t they deserve to have ‘normal’ holidays since they haven’t gotten addicted to meth and gone to prison?

It’s not just about him all of the time.

No, it’s not, but may you never know the pain of missing one of yours like this.

My son told me that he wakes every morning now to silently practice ten minutes of gratitude before moving off of his bunk— it is the only way he can face another day, he says.

I applauded his commitment, knowing my approach to gratitude is less enthusiastic these days. My former therapy clients would be in shock. For years, I ended each session by asking them to write something for which they were grateful on the wall before they left. That list stayed up as a running record of the good things that they had found in the dark. I only ever wrote one gratitude on that wall when a 7-year-old demanded that I play along—

I'm grateful for my kids, I had written.

The Presently app on my phone tells me that I have logged over 515 gratitudes to date— a practice I officially started some time after my son went in. Admittedly, most are infinitesimal blips of recognition like “the weather” or “good coffee.” More than that, it has become a record of the things that I have been forced to reframe.

‘got a letter’

‘got our visits back’

‘he's in a better facility’

Pop psychologists and insta-gurus tell us that we can extend our lifespans and beat disorders with a gratitude practice, but you know what, I am really just out here raising a tiny middle finger before bedtime every night.

“What are you grateful for today?” it asks.

‘That I haven’t lost my mind yet.’

Gratitude-through-grief is not cute. No, some days it might be more appropriate to visit a rage room and beat an old cellphone with a baseball bat or break what look like grandma’s heirloom dishes against a wall because at least then there would be movement here. At least then I could be honest instead of wallpapering over the mess with gaudy decoupage flowers:

‘My adult son got outside today’ (Woo-hoo)

‘I started a blog about my son’s prison time’ (Just what I’ve always dreamed of)

‘He is getting dentures at 27’ (Frickin awesome)

Madness, every bit of this.

I want to tell those mental health influencers that they can shove their November gratitude posts— the ones with AI-generated twenty-somethings posed over leather journals in fake coffee shops. You don’t know how much of a grind gratitude becomes until addiction or prison or death takes your kid away.

For me, ‘gratitude journaling’ is manual labor deep inside a pitch-black coal mine, candle headlamp and all.

My husband tells me that I've become ‘addicted’ to depressing things, and I would like to think that means that I am introspective and deep like Eddie Vedder or Sean Penn or Mary Karr but based on his tone, I am pretty sure that is not at all what he means.

I am not addicted, but my behavior these days might be classified as heavy use. Three books on my nightstand have the word prison in the title. I’m researching the history of solitary confinement, for God's sake, and I started a full-blown manuscript this month about how I watched my son go to prison. Even this blog is like that camera box affixed to the railing of a rollercoaster that snaps my face in intervals along the terrifying climbs and sickening plunges of the ride. This month, I am in a free-fall toward a tunnel.

Sorry about my face, but I’m not having fun.

Frankly, I did not know how personally I would end up taking those prison area signs. I had no idea that I could love the boogie-man this much. I certainly never imagined there would come a day when I would very much like to pick up a prisoner from a dark row of trees on a rainy, autumn night. I only fear how far I might go to give him one day beyond those fences— one holiday home, one plate of hot, cheesy potatoes.

There are still many days that I am stifling an existential scream, both for him and for myself. After one of my early visits, I turned back out on the road outside of the prison and began punching my console, repeatedly screaming WHY?! over and over at the windshield (while driving 65 mph). I could hardly see the road through my swollen eyes. That’s the real reason you should use caution driving near prisons— there are moms out there losing their minds on those roads. Of course, this happened before I realized that he would miss my funeral if I crashed doing some dumb shit like that.

I cry mostly at home now.

On a podcast this week, I handled myself with poise until the very end— ‘Have there been any moments that have given you hope?’ the podcaster asked. ‘Yes,’ I began and then my voice waffled, ‘When my son talks about finding a wife and having children some day.’ I broke a little, and then apologized and cleared my throat.

But, apologies are not in order. It is important for me to see beyond this stretch of road.

Gratitude #516 should be something about realizing that ‘this too shall pass.’ Number 517 is for the woman who will love my son some day, in spite of his past. Number 518 is for those precious grandkids who already give him hope, those tiny faces who will only know him after all of this is over— God willing.

And #519 is for the people who keep my eyes open when I am plunging toward darkness— for those of you who are reading and sharing and supporting our journey. I'm so honestly grateful for you this month. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

P.S.— Whether you love or hate gratitude ‘practicing,’ will you leave us something in the comments? All thoughts are welcome here.

There is something to be said about gratitude, but I often sit in the camp of: can we just say this fucking sucks? Because lots of things in life really flat out suck. And I think we miss the boat if we are constantly in gratitude. I am mostly an optimist, but also a realist. Sometimes shit just sucks and there is no way around it.

Also, I would love to get together with you in a room and smash some shit with a baseball bat! A few months ago I bought a punching bag and it has been the best thing I have ever done. I have somewhere to take my rage and it feels so good.

You get to be "addicted to depressing things", angry and grateful all at once. Or not grateful if you don't feel it.

My point of view (and I don't live with you, so I know it's different), but I see you as someone dedicated to a fight. And with that comes rage, grief and all of the things.

Trust that whatever feelings come up for you are right. Maybe we should create a "This Sucks" journal. Haha.

I have gratitude for your very muscular middle finger. You are brave and strong and smart. We are fortunate to have you and your mood wailing on these facts and figures that demonstrate the failures of our criminal justice system.