Confession #15: Dads Matter

3-Inch Pumps, Rampaging Elephants, and A Baby From New Orleans

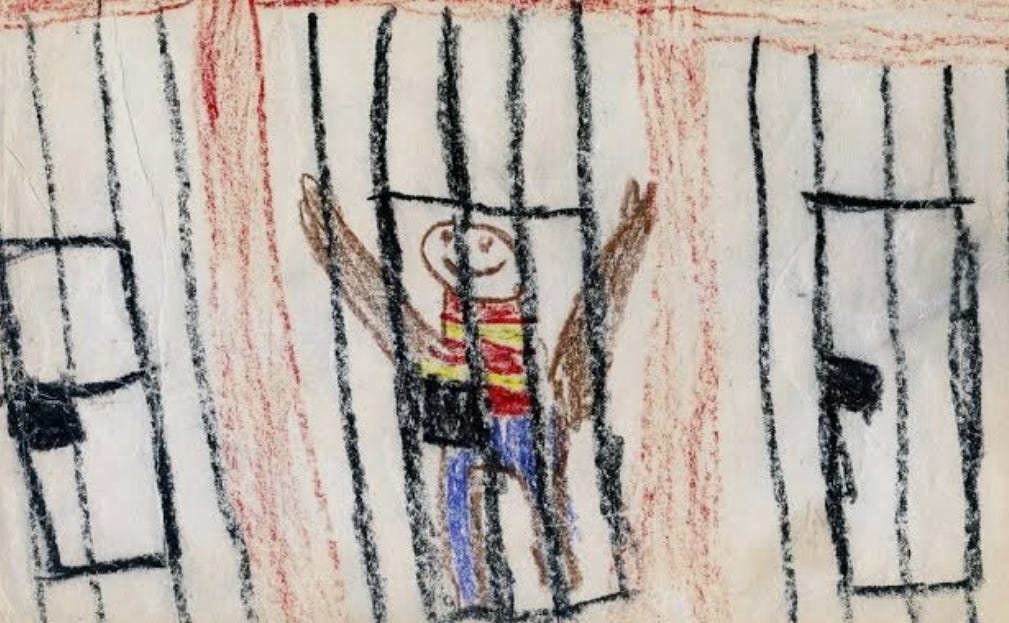

I don’t know what I expected the first time I visited my son in prison, but it wasn't the 3-inch red vinyl heels that teetered across the waiting room floor. Nor the young kids trailing behind them.

Let's not judge.

In a place that will turn you away for a rip in the knee of your jeans— tank tops, white T-shirts, skirts above the knee, shorts, and all form-fitting (or excessively baggie) clothing items are strictly forbidden. That woman in the pumps was giving her husband the only visual he is allowed to have in our State prisons while carrying the full weight of their three children.

Every prison visiting room is polka-dotted with moms, grandmas, wives, sisters, daughters and girlfriends. Though it's often tense— we find small moments to offer each other softness. A ragged sigh, acknowledged. A stupid new policy, clarified. A generous “I love your jeans” or “have a good night, drive safely.”

One night, over the roar of pee streams that had been held back for over two hours, I heard a woman in the next stall say that this was “the last time” that she will support her husband through any more of his legal shit (he only had a few months left on his sentence). At the sink washing our hands, her face told me that she meant it. It wasn't fair what his addictions had done to her. None of this is “fair” to us—

After several weeks of those early visits, one afternoon I leaned over and asked my daughter who sat there with me, “Where are all of the men?”

She rolled her eyes.

For every ten women in the prison waiting room, you might see one man bouncing his knee violently, eyes glued to the blaring TV. It's usually a grandpa or an attorney or a brother, though. Dads just do not visit prisons.

I think I saw three fathers (total) in all of the time that I was allowed to visit my son. One was my son’s father. One was the dad of a recently convicted 17-year-old who got 40 years for killing someone in a DUI accident the night he got his driver’s license. The other dad was a tired looking man in a tie-dyed T-shirt with a thin grey ponytail.

As I mentioned in a recent post, 80% of the incarcerated population is male. In another post, I mentioned that it is women who are supporting these incarcerated men to have phone calls and commissary and human connection— a staggering 83% of the time.

Which is a total rip-off since it is the scarcity of healthy men that perpetuates this cycle to begin with. Strong, independent women and great fathers aside— 20 million U.S. children live in a fatherless home right now.1 And the rest of the story can be found in a school counselor publication—

71% of all high school dropouts come from fatherless homes

85% of all children with behavior disorders don’t have a dad at home

90% of homeless and runaway kids left their mom’s house

60% of youth suicides experienced fatherlessness

85% of all youth in prison did not grow up with a dad at home

Rampaging

One of my favorite textbooks in grad school explored the research and outcomes of a decade of work in Pilanesberg National Park, South Africa.

In the 1980’s, the park was born out of Operation Genesis— one of the largest game translocation projects attempted in that continent’s history. Spearheaded by Dr. Salomon Joubert, a South African ecologist, the goal was to convert degraded farmland into a protected wilderness and to re-populate the area with native plants and animals.

Many of the animals picked for the new park were brought in from neighboring areas of South Africa but when it came to moving the elephants, ground crews realized that capturing and relocating adult males (who weigh between 4,000-15,000 pounds each) over a distance of 500 miles was a logistical nightmare— not to mention an expensive one. The decision was made that only elephant babies and young calves would be relocated, but after a sub-optimal start for these toddler groups they started moving mamas with their young offspring. The adult males were still not invited to the party.

Leave it to the humans to destroy natural order.

Within ten years, the park had a serious problem. In 1993, a tourist had been killed in an aggressive rampage by adolescent male elephants and the carcasses of over 50 brutally murdered rhinos were found all over the region. The adolescents were completely out of control, killing with a level of intentional mutilation uncommon for their species.

After public concern rose and park management held a series of think-tanks on elephant hormones, elephant development, and how bad this whole thing looked in the media, the team was forced to either castrate these young bulls or find a natural deterrent to destructive elephant behavior. Turns out, there was one thing that could make all the difference—

Adult males.

Within hours of introducing just six adult males to the herd, the wilding-out completely stopped. No more murders, no more carcasses, no more trees or fences being savagely attacked. Even the infighting among the gangs of youth stopped.

The human psychology lesson was that the presence of strong, healthy males can provide guard rails for wayward and dangerous adolescent behavior. Because the period of elephant adolescence tracks with that of Homo sapiens (spanning the chronological ages of 13-20) we might make some keen observations for our own species.

While moms are essential and we serve 1,000 developmental purposes in the life of our children, we alone cannot redirect the biological idiocy of young males.

And Yet

It's estimated that over 33% of current inmates had at least one parent who was incarcerated during their childhood. That means one in three men in prison grew up missing a parent due to generational legal troubles. Between 1991 and 2016, the number of fathers in prison increased by 48%.2

This Father’s Day, there are over 600,000 fathers behind the fence, leaving 1.5 million U.S. minor children without a dad in the backyard. Worse still is how swiftly the dominos fall. Research indicates that adolescent boys often develop aggressive and anti-social behaviors within 2 months of their father’s arrest.3

And we still think the “tough on crime!” politicking game is helping us.

But— you say, so many people have rough starts and they become successful adults. Yup, I am one of them.

As a child of the 80’s, I lived the technicolor absent-father experience. I can count on my hands how many times I saw my biological father between the ages of 3-18 and he skipped so hard on child support that my pervert stepfather was able to move in and adopt me when I was in 3rd grade.

That guy (the one I was made to call “dad” for 5 years) was later sentenced to 30 years in prison for 8 counts of CSC. Before he was caught and put in prison, my mom was arrested and charged for allegedly attempting to have him killed for his disgusting behavior. We all made the evening news— and it was one hell of a 7th grade year.

I changed my last name back to my birth father’s when I turned 18— after all of his child support had been spent on booze, cigarettes, and other women. He died in 2010, after we had some time as adults together in the world. He met some of his grandkids and we enjoyed a few backyard gatherings. He had gone into DTs when he was admitted to the hospital, so we got a few weeks of him off of alcohol before he died— though the morphine provided a convenient buffer.

While he laid in the ICU with sepsis creeping up his leg, I drove two hours everyday to sit with him and feed him ice chips. One afternoon when I rounded the doorway he looked up and said, “You shouldn’t be here, you should be with your family. This isn’t about you.” I think he was trying to be selfless.

Blessed with his quick wit I responded, “It has never been about me, dad.”

He was placed in a coma a few days later, from which he never awoke. In hindsight, I do not believe that I was ever afforded one sober conversation with my dad in my lifetime. In somewhat related news, my pervert stepdad is back out on the streets, in that same small town, doing whatever perverts do when the System kicks them back into our population without treatment and support.

PACES

There is only one man above me in my family line who deserves to be celebrated this weekend— the one who stepped in when the primary adults in my life were incarcerated or headed that way.

It is true that many children of incarcerated parents go on to live meaningful, productive lives but they don't do that without positive adults intervening. Though my ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) score is a whopping 8, my PACE (Protective and Compensatory Experiences) score is a perfect 7 out of 7, largely because of my grandparents. My grandpa became our 15,000 pound elephant overnight, without hesitation or complaint.

He provided a safe home and a steady presence. He drove us 8 hours for supervised visitations. He made us into Detroit sports fans— which, in and of itself, is character building. He shot hoops with us in the driveway. He told us, repeatedly, how important education was and he showed us how to use a computer and a dot-matrix printer. He got up before dawn, every day, to read, pray, and run in silence before he made a fresh cup of coffee to bring up the stairs to my grandmother in bed. He was disciplined and reliable.

I never-not-once witnessed my grandfather drink alcohol, smoke, or even eat too much and only once ever did I hear him swear— when that pervert stepdad of mine had the balls to roll up onto grandpa’s front doorstep and try to take us kids with a court order.

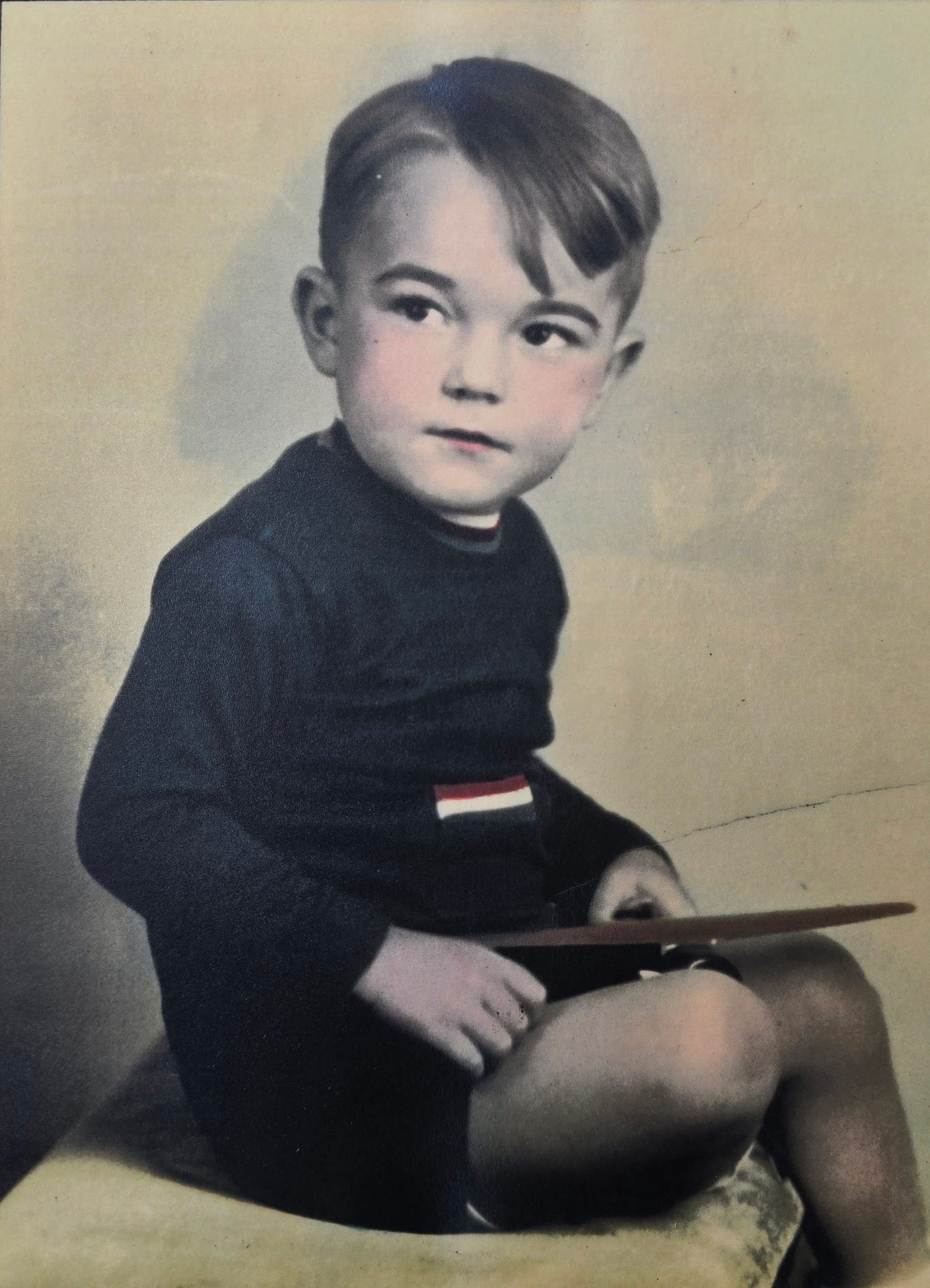

My grandpa didn't discuss his own childhood, and he would shudder at the lurid details that his oldest granddaughter now willingly puts out into the world about our family. My casual use of 4-letter words alone would result in a handwritten cease and desist letter citing memorized Bible verses. I only picked up on the gist of my grandpa’s childhood through his cautious omissions and my grandma’s occasional leak of scandal. I pieced together hard facts through Ancestry.com much later on:

There was a young couple from New Orleans who relocated to Detroit in 1929 after being married for only a few short months. By May 1930, the young man had contracted meningitis and died within days. He left his beautiful 19-year-old wife there— two months pregnant and over 1,000 miles from home. She is listed in the 1930 census back in Louisiana with family and a New Orleans stamped birth certificate from November 1930 brings my grandfather on the scene. Though he was named after him, Grandpa never knew his dad.

My great-grandma remarried when my grandpa was 7. They moved back to Detroit where he was raised in alcoholism, clouds of cigarette smoke, and fist fights with his overbearing stepdad. At 18, he enlisted in the Marine Corp, leaving home as fast as he could. He would win the hand of Ms. Detroit over his arch-nemesis track buddy whom you may know as Tom Skerritt (aka Viper in Top Gun). The real tea is that my grandma said my grandpa was the better kisser— and I can only write that because both of my grandparents are now in heaven. Sorry, Tom.

I do not have permission to discuss the outcomes of my father’s absence on other family members, but suffice to say there was a great deal of rhino attacks and rampages after he absconded. Forty plus years later, my siblings and I have done the work necessary to evolve and live as sober, law-abiding, contributing members of society, as well as mindful parents to our own kids— and I give my grandfather credit for much of that. He was not perfect, but he was intentionally present.

Dads Matter

In 1993— the same year of the adolescent elephant murder of a human in Pilanesberg National Park— a volunteer group of women brought in boxes of greeting cards to be donated to Terminal Island federal prison inmates near Los Angeles. The cards were offered to reduce the cost barriers of communicating with family members on the outside.

A late-comer to the table of free cards, inmate John Orr was surprised to find a stack still available after the majority of his tier had already made their selection. As he rummaged through what was left, he shared in his poignant essay that he found only the Father’s Day cards left behind.

And there you have it— dads matter until they don't.

Learn more in Irreplaceable (the documentary). Or visit U.S. Census records online.

I know this is ultimately about your experience with your son being incarcerated, but I just came to say how sorry I am for the trauma you endured as a child. And thank goodness for your elephant grandad.

I cannot imagine what they went through as grandparents and ALL the issues that piled on their hearts in the 90's. How they stood so strong and steadfast is a value I still need to find. I always noticed that when we walked into their home, grandma went right for my husband! She admired a strong family man. If he was missing...well, the kids and I were second best. Where is he? Working?! Okay...give him a hug for me, next time he needs to be here 😉. Look at their family line now and ALL the cycles we are trying to break 😊 Horrific childhood events (that we still live with) and somehow... overcoming. I give so much credit to them. Our mothers, through life altering events, were endlessly supported by a strong parental, spiritual duo.